The 1987 celebration of the school centennial brought into sharp focus three elements that help explain the school’s success in its first hundred years, and in its journey well into its second century: a commitment to educational excellence, a distinctive mission that was refined over time, and strong leadership and community support. By standing on the shoulders of Anna Head and all those who led the school in its first one hundred years, faculty, administration, staff, students, parents, alumni and the boards have built on that legacy to make the school what it is today.

A Century of Excellence

While preparing The Head-Royce School: A Centennial History, 1887-1987, we learned from the California Association of Independent Schools (CAIS) that our school was one of just half a dozen founded in the 19th century that were still operating in the 20th century. In Northern California today, Head-Royce is the third oldest independent school, following San Domenico School founded in 1850 and the Hamlin School in 1864. How did the school develop the resilience to endure and thrive over all those years?

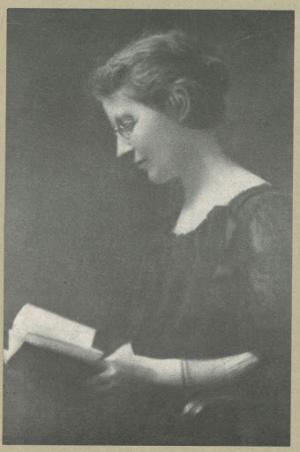

Anna Head herself established a compelling vision for a new academy in Berkeley, originally called Miss Head’s School for Girls. A contemporary of the legendary, progressive University of Chicago educator John Dewey, she was very well educated, steeped in experience gained from teaching and traveling the world, and determined to create an excellent new school. Born in Brookline, Massachusetts in 1857, she came to the Bay Area in 1868 after her father, a graduate of Harvard Law School, had moved west to establish his practice and later became a Superior Court justice. Anna Head’s mother provided a strong role model as a teacher in San Francisco and Oakland, where she established a small French and English school for young children in her home near DeFremery Park in West Oakland. Anna Head graduated from Oakland High School in 1874, studied music in Boston for a year, and then returned to UC Berkeley where she graduated in one of the first classes in 1879, one of 23 women in a class of 177 students.

By the time Anna Head had finished nearly a decade of travel in Europe and study in Greece, she had formed a clear, progressive philosophy of education. At age 30 she set out to start her new school, initially located in a home at the corner of Dana and Channing in Berkeley. Anna Head retained her cousin, the architect Soule Edgar Fisher, to design Channing Hall, a handsome Queen Anne building, one of the first of the classic Berkeley brown-shingle buildings (and today on the National Register of Historic Places). With funds from her mother’s sale of her Oakland school, Anna Head opened the new school in the 1892-93 school year, and over the years she added several structures on the campus. The early catalogs describe a rigorous core curriculum, including four years each of English, math, a foreign language, and history. Her love of nature led her to recommend a fifth solid in science (botany, zoology, and physics), courses “determined on the principle that one fact learned from nature is worth a dozen learned from books.” She recognized the value of the arts “to increase the powers of observation of each student.” Regular physical activity was offered in “cheerful and inspiring exercises” including horseback riding, dancing and games; notably one of the first women’s basketball games ever recorded was played between UC Berkeley and the Anna Head School, which won the game 4 to 3! Anna Head announced that her school would prepare young women for the most outstanding colleges and universities in the nation. Importantly, she stressed that “the health of the girls will be the first consideration.” Headmistress for 22 years, Anna Head was a real polymath and an inspiring teacher, offering instruction herself in English, Latin, Greek, history of art, psychology, and zoology. After her retirement, she was often seen gardening in the English cottage she built on Belrose Avenue in Berkeley and had a continuing influence on the development of the school. Looking back on the first century of the Head-Royce School, it is clear that it was “the lengthened shadow” cast by its founder Anna Head.

Anna Head secured her legacy when she passed the baton of leadership and sold the school to Mary E. Wilson in 1909. Serving for 29 years, Mary E. Wilson guided the school through tumultuous times, including World War I and the Great Depression and helped develop a national reputation for the Anna Head School. Raised in Montana, she graduated from Smith College in 1891, earned a master’s degree in English from UC Berkeley in 1896, and began teaching English at a San Francisco private school. In 1901, just after the school year finished, she joined her friend Annie Montague Alexander on a historic, 10-week geological expedition to Fossil Lake in Oregon. According to Colgate University geologist Connie Soja, the two women “headed for the ‘sagebrush desert’ of central Oregon” with two university geologists, “trekked for more than 3 weeks and crossed 300 miles of sparsely inhabited country,” and collected a variety of Pleistocene, or Ice Age, specimens, “including fossils of extinct camels, horses, ground sloths, mammoths, dire wolves, and others.” Annie Montague Alexander went on to help fund and found the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology in 1908 and the Museum of Paleontology in 1921, both at UC Berkeley. Having been raised as a young girl in the Big Sky country, Mary E. Wilson evidently developed a great deal of grit and determination that would serve her well in the years ahead. When the 1906 earthquake destroyed her school in San Francisco, Mary E. Wilson joined the faculty at Miss Head’s School for Girls that fall to teach English. Three years later she purchased the school from Anna Head. Inheriting approximately 150 students including 35 boarders, Mary E. Wilson worked hard to shape the future of the school, which she officially renamed the Anna Head School in 1919. She constructed additional facilities and reorganized the school into three departments—Primary (5-8), Intermediate (9-13) and Upper (14-18), plus a post-graduate year. She added uniforms, a daily chapel that lasted through the Sixties, started the yearbook Nods and Becks, created a Student Council, and expanded the athletic program. Two of her most famous graduates were Helen Wills Moody ’23, who won the Wimbledon tennis championship eight times, and Helen Jacobs ’26, who won the U.S. Open four times and Wimbledon once. They had a fierce and sometimes contentious rivalry begun on the courts of the Berkeley Tennis Club, as I discovered in 1987 when I invited them each to campus for the Centennial; both politely but firmly declined, and I sensed that these two remarkable women still felt the emotions of their athletic competitions so many years ago.

Mary E. Wilson embraced Anna Head’s progressive educational philosophy, offering a program centered around a “well-balanced life of earnest study, outdoor sports, and the cultivation of a delight in music and the other arts.” She also emphasized her strong “desire to develop character.” With her encouragement, the students engaged in many service projects over the years, notably raising money for Armenian famine relief and sewing clothes for Belgian school children in the First World War, making masks during the flu pandemic of 1919, and helping to board students after a devastating fire in Berkeley in 1923. During the Depression, when a number of private schools in Oakland and Berkeley were forced to close, Mary E. Wilson is reported to have waived tuitions for those unable to pay, funding the scholarships out of her own retirement savings. Her reputation as an educational leader went well beyond California. In 1919 Mary E. Wilson was elected president of the National Association of Principals of Schools for Girls (NAPSG), and she served as president of a number of other organizations, including the Smith College Society of Northern California, the Fortnightly Club, and the Berkeley Town and Gown Club, was vice president of the Pacific Coast Association of Collegiate Alumnae, and belonged to the Claremont, Mount Diablo, and Orinda Country Clubs, as well as the Young Women’s Christian Association and the American Association of University Women. Clearly a leader in her profession and well connected in the community, Mary E. Wilson modeled for her students the civic engagement she expected them to pursue.

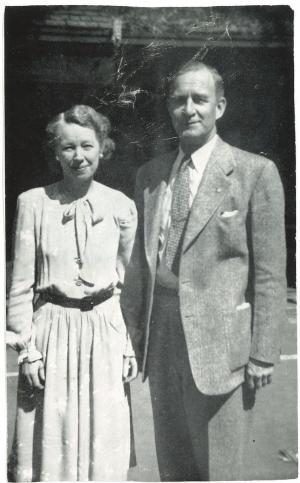

As Mary E. Wilson approached retirement in the late 1930s after 29 years heading the school, she formulated a plan to ensure that the school would continue. Years earlier she had met and befriended a fellow Smith alumna, Lea Hodge, a young widow with three children teaching English at the Helen Bush School in Seattle, and she arranged for the children to board at the Anna Head School. As Mary E. Wilson anticipated retirement, she met Lea’s second husband, Theopholis Rogers “TR” Hyde, a Yale alumnus with a long career in private independent schools. He taught at the Taft School and the Hill School in the East, and he then served as headmaster of Chestnut Hill Academy in Pennsylvania and Bolles Military School in Florida. She convinced them to buy the school in 1938, thus beginning nearly three decades of husband-wife leadership during the “proprietary years” when the school was organized as a private enterprise. As a couple, they brought extensive school experience and a desire to develop the school community. Living in a cottage on campus, the couple was available always to counsel students, encouraged student leadership with the development of the Student Court, and periodically they took girls to their “Hyde-Out” in the Santa Cruz mountains to encourage their love of nature. The Hyde years were soon shaped by America’s entrance into World War II in 1941 as TR was commissioned as a Lieutenant Commander in the U.S. Navy, and Leah ran the school for three years, largely on her own. The war had a profound impact on the students’ awareness of their place in an increasingly interdependent and complicated world, as they noted in the 1942 Nods and Becks. “This has been a year to be alive in. It has been a time of portent, of change,” the editors wrote, offering their book as “a record of our small part in the history being made today.” After the war the Hydes began to make preparations for their own retirement and explored restructuring the school as a non-profit corporation along the lines of the East Coast schools they were familiar with. Although it would take nearly two decades for that to become a reality, the Hydes clearly understood the changes that would be required for the school to survive.

Like their predecessors, the Hydes hand picked their successors, Daniel and Catherine Dewey, who bought the Anna Head School in 1950. For those of us at the school in the “modern years,” their impact was legendary, as we learned the story of how they guided the school over 15 years through a period of profound change until 1965. Both came to their work with a zeal for education. Dan Dewey was raised in Milwaukee, attended Williams, and did graduate work in classics in Athens. Catherine grew up in Pasadena, attended Stanford, and met Dan in Athens, where she studied archaeology. After their marriage, Dan taught Latin, Greek and history at Mills College, while Catherine was raising their four daughters. Two of their children were attending the Hyde’s school, when they learned of the opportunity to buy the school. As school leaders they were fondly remembered. Catherine ran the Lower School and did admissions, while Dan ran the Middle and Upper School and taught history. Under their leadership, the school began Advanced Placement instruction in English, French and Spanish and added the American Field Service program to promote international understanding. The Deweys began the effort to integrate the school when they admitted the first African-American student in 1956, Joyce Boykin ’68, just two years after Brown vs. Board of Education. She later credited the Anna Head School with the very strong education that led her to become a physician in Southern California, but she also recalled the racial intolerance among some parents at the school when she was a student.

In 1955, the Deweys faced a major challenge to the school’s existence. The University of California Berkeley announced they would be taking over the school through right of eminent domain as they anticipated expanding the university campus southward. Quickly, the Deweys created an advisory board to consider the options, and in 1957 they incorporated the school and established a board of trustees to establish a new governance model. Over the next seven years, the Deweys led the exploration to find new property, eventually settling upon the site of a chicken farm six miles away on Lincoln Avenue in Oakland. They helped raise over $1 million to build the new campus, select Corlett and Skaer architects to design the modern, wood-frame structures, and float personal loans to complete the initial funding. This was no easy task. The school’s lore suggests the project ran short of cash, there was not enough money to complete the flooring in the Mary E. Wilson Auditorium, and the outdoor pool was shortened to 20 yards to save dollars.

During spring break in 1964, the school moved to the new campus, and a new era began. Alumnae from that era report that the move was quite a jolt, as they adjusted to a school campus that was barely landscaped and “out in the country.” In retrospect, however, the move probably saved the school. That fall Mario Savio and thousands of UC Berkeley students mounted the Free Speech Movement at Sproul Plaza just three blocks away from Channing Hall. Nearby Telegraph Avenue became a center of the counterculture in the Sixties. In 1969 during antiwar protests at People’s Park adjacent to the school, a Berkeley student was shot and killed, and the former school campus was awash with tear gas. University campus unrest continue for years thereafter, so in many ways, the Deweys leadership and decision to move the school secured for it a place where learning could continue in a turbulent world.

Over the next 20 years, the school moved through a period of transition in a time of educational and cultural upheaval. The five school heads grappled with the significant decision to coeducate the school and to respond to the dramatic educational and cultural changes brought about by the civil rights, women’s and countercultural movements, and the Vietnam War. After Nancy Gilmer served as a one-year interim school head, Art O’Leary was selected as the new head and served from 1967 to 1974. Reflecting on the challenges when the school was forced to move, he observed that “it was faced with extinction,” only saved by “the foresight and generosity of the Deweys” and the heroic efforts of the board headed by Kay Connick Bradley ’33. A warm-hearted man, Art O’Leary worked to maintain the “Anna Head Traditions” including uniforms, hemlines that “we tried to hold at ‘one inch above the knee’,” and chapel in a Judeo-Christian community. But at the same time, he was clear eyed about the school’s “financial realities” as “too much of the tuition income was going to service the debt,” which amounted to $600,000 and a $45,000 annual payment. Fortunately, the board, inspired by new trustee Betty Bechtel, led a successful fundraising campaign to “burn the mortgage.” Still, Art O’Leary recognized there was a structural problem with faculty salaries below market average, and he initiated a fundraising initiative to improve compensation and created a salary scale to ensure “openness and equity.”

The greatest issue facing Art O’Leary and his board was coeducation. Across the country in the 1960s, colleges, universities and K-12 private schools began to abandon single sex education and adopt coeducation. For more than 80 years, the Anna Head School was philosophically committed to the benefits of an all-girls education, but the growing women’s movement was calling for access to all male institutions. In the late Sixties the school was graduating just over 20 seniors, admissions and tuition revenues were down dramatically, and, as I later heard, trustees had to write personal checks in 1967 just to make payroll. An advisory board recommended creating a coordinate school for boys, and board member Edith Mereen ’13 suggested the name Josiah Royce, Anna Head’s brother-in-law. The school began a quest for more property, entering into initial negotiations with the Mormon Temple for the eight-acre parcel of land uphill, but eventually they settled upon renting facilities across the street from the Lincoln Child Center. In 1971, the Royce School for Boys opened with 27 students in grades seven to nine. As Art O’Leary observed, “The early years of Royce were difficult ones, and the new school tended to drain the resources of its older and more successful sister.” Nonetheless, the schools shared a vision that “coordination would provide the best of all worlds; it would preserve the best of the old, while moving the schools forward into a stronger position for the future.” Art O’Leary shared the ambivalence of many alumnae about the change, but in the final analysis, he gave “the edge to coeducation” in the belief that “the changing concepts of the roles of women that the past few years have developed make it more possible that girls will explore their capabilities in ways, perhaps, which only Anna Head could allow them in past years.” Indeed, the decision to coeducate carried lasting implications for the evolution of the school, and created the continuing challenge that boys and girls, young men and women receive an equal educational opportunity.

With the decision to create a coordinate boys school, it fell to Rick Schroeder, headmaster from 1974 to 1977, to help create a fully coeducational institution. As he wrote, “The Head Royce Schools could not escape from the country’s mentality of troubled times. In 1973-74, the school’s operating deficit was more than $90,000, the endowment meagre….The only way to relieve fiscal hardship at Head-Royce was to increase enrollment without adding appreciably to the school’s operating costs.” He moved quickly to accomplish that goal, principally by integrating the instruction for boys and girls and moving away from the perception that the two schools were only affiliated. As a result, enrollment soared from 375 in 1974 to over 500 in 1976. In addition, a coeducational kindergarten was added in 1975 in a small farmhouse on the east side of the campus. Rick Schroeder favored a rigorous, required curriculum and dismissed the elective program as a “potpourri, a discordant medley of odds and ends, bits and pieces.” With his encouragement, the Upper School adopted a two-year required survey of Western Civilization. But as his short tenure ended, he was aware that the school’s situation continued to be fragile: “By the spring of 1978, endowment had yet to be raised…and the school continued to be dependent on the Lincoln Child Center.”

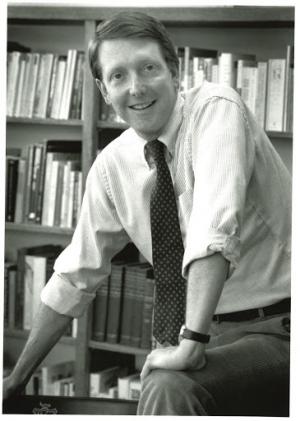

When Gardiner “Gardie” Bridge arrived at Head-Royce, initially as an interim headmaster, and during the seven years of his tenure, he brought deep educational experience to his work to help the school achieve a new level of financial security and community cohesion. He was steeped in the independent school tradition, having attended the progressive John Burroughs School in St. Louis and Dartmouth College, as a teacher at Hebron Academy in Maine, as Director of Admissions at Trinity College, and as the founding head of the new University School in Milwaukee, a merger of three separate independent schools. As he noted, “A needed goal for the school was to achieve a sense of oneness, a sense of community.” He reorganized the school into three distinct divisions, including Lower School (K-6), Middle School (7-8), and Upper School (9-12) and convinced the board to adopt the name The Head-Royce School to signal that it was one K-12 coeducational school. He built a strong and loyal administration of division heads, a business manager and development director, and together they ran a successful capital campaign to build a Middle School on campus (it was later renovated and is now the Read Library). He said about the faculty, “When I first came to the school, they believed that the only way to get their opinions across was to administer their own affairs.” Over the years, he worked to establish the administration’s authority to lead the school, developed the department chairs and Curriculum Committee, and increased the level of “oral and written communication.” Indeed, as I discovered, the personnel files from his tenure were filled with long, thoughtful letters of praise, and admonishment, written in a beautiful hand, always respectful, and sometimes very direct; they did provide a source of rich detail whenever I was called upon to deliver a faculty roast! As I prepared to succeed Gardie Bridge, he played a key role in whatever success I experienced. In the early eighties, I remember he attended a workshop that I offered at the California Association of Independent Schools regional meeting on teaching Advanced Placement American History, and afterward he proceeded to tell everyone within earshot what a “really great presentation” I had given. I sought his advice on whether to apply for the position, and he was a steady support throughout the transition and in the years that followed.

In 1983 as a candidate to become headmaster, I studied Head-Royce and knew in its recent past it had been buffeted by the forced relocation, fragile finances, the move to coeducation, rapid turnover of heads, and a sometimes fractious board-head relationship. I could tell the school was making progress toward becoming a vibrant, K-12 coeducational independent school. But, I also became aware that it faced continued challenges—a lean budget, lack of endowment, faculty salaries that were below average, a development program that was underperforming, questions about board and parents association governance, under-enrollment especially in the Upper School, a curriculum that seemed to lack overall coherence, a tentative attempt diversify the school, a sharply critical accreditation report in the late Seventies, and a lack of visibility in the wider educational community, to name a few.

Yet, I was also aware that over 96 years, the school had demonstrated tremendous resilience. Coming from one of the newest independent schools in the Bay Area, I was excited to join that historic tradition. From this survey of the school’s first century, it is clear that the individual school heads had a significant impact on the evolution of Head-Royce; remarkably, there have been a total of eleven heads with an average tenure of twelve years over 130 years. During that time, the nature of the position changed as the school evolved from a proprietary academy owned and operated by the headmistresses and headmasters to a corporate, non-profit structure with the school heads serving as chief executives. Reflecting on the years that unfolded after the Centennial in 1987-88, I think several factors contributed to the continued growth and success of the school: a memorable mission, a growing tradition of best practices in leadership and good governance, and a building commitment to the school’s transformation.

A Memorable Mission

From the school’s catalogs and publications over the years, one can derive an underlying educational philosophy and mission. After I arrived, the board approved a philosophy and mission statement as part of the strategic plans in September 1984, and again in December 1987, as we sought to define our core beliefs, practices, and distinctiveness. Nonetheless, in 1988 the visiting committee for the Western Association of Schools and Colleges, which was conducting the regular evaluation site visit, specifically recommended that the board and administration “clarify and publicize the philosophy and goals of the school, with particular reference to a college preparatory curriculum and whole child education.” As a result, in 1990 the current mission was crafted and approved by the board of trustees. One day during this process, Development Director Diana Odermatt came into my office with a present, Peter Drucker’s just published book, Managing the Non-Profit. The former Dean of Admissions and Financial Aid at Mills College and previously a Head-Royce trustee, a skilled and experienced leader, she always gave me very good advice: “I think this book might be of some help in recrafting the mission.” As the opening chapter declares, “The mission comes first….the first job of the leader is to think through and define the mission of the institution.” According to the National Association of Independent Schools best practices, “The board of trustees is the body that delineates the mission….to maintain a school’s integrity, the school’s mission should be the guidepost for all major decisions.”

With a small group, but with considerable community input, we created a new mission and philosophy for the school, one that was succinct, memorable and based on the best educational wisdom to articulate our progressive, whole child philosophy and vision of educational excellence. At its December 1990 meeting, the Board’s Educational Policies Committee chair, UC Berkeley professor Ed Blakely, proposed the final draft, which was unanimously approved. And the Head-Royce Newsletter announced the new mission to the school community as a “clear, concise, and much strengthened charter for the School.” The mission was significant because it declared the school’s commitment to three core values—scholarship and academic excellence, respect for diversity, and constructive citizenship—that would inspire and shape the direction and evolution of the school for years to come.

The mission revision also allowed us to explain our progressive commitment to “educate the whole child.” In 1983 Harvard psychology professor Howard Gardner published Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences, and it provided the rationale for our liberal arts program. After hearing Gardner speak at the National Association of Independent Schools annual meeting in 1988, I reviewed his book in the Newsletter, observing that his “work highlights our efforts at Head-Royce to provide a comprehensive education of the whole child from kindergarten through 12th grade.” Gardner’s “intelligences” as he developed them over time included: verbal-linguistic (word smart), mathematical-quantitative (number smart), bodily-kinesthetic (physically smart), musical-rhythmic (sound smart), visual-spatial (picture smart), interpersonal (people smart), intrapersonal (self smart), naturalist (nature smart). These eight abilities provide the philosophical underpinning for the educational goals identified in the mission.

A decade later, when questions arose in the community about whether our commitment to diversity and academic excellence were in tension, the board reviewed and reaffirmed the mission. And in 2007, after new emphasis emerged on citizenship, global education, and environmental sustainability, the board made a few simple additions to the mission. The clarity and distinctiveness of the mission has indeed been a critical element in the school’s success.

The Head-Royce School Mission

The mission of the Head-Royce School is to inspire in our students a lifelong love of learning and pursuit of academic excellence, to promote understanding of and respect for diversity that makes our society strong, and to encourage active and responsible global citizenship.

Founded in 1887, Head-Royce is an independent, non-denominational, coeducational, college-preparatory, K-12 school, which offers a challenging educational program to educate the whole child. The School nurtures the development of each individual student through a program that seeks:

- to develop intellectual abilities such as scholarship and disciplined, critical thinking;

- to foster in each student respect, integrity, ethical behavior, compassion, and a sense of humor;

- to promote responsibility and leadership, an appreciation of individual and cultural differences, and a respect for the opinions of others;

- to nurture aesthetic abilities such as creativity, imagination, musical, and visual talent; and

- to encourage joyful, healthy living, a love of nature, and physical fitness.

All members of the Head-Royce community strive to create an educational environment that reflects the School's core values of academic excellence, diversity and citizenship, one in which each student can thrive. We believe that a program based on these core values will prepare our students to be effective citizens as they face and embrace the challenges and the opportunities of the future.

A sense of history, a clear, compelling and inspiring mission, and a culture of collaborative leadership—these were the qualities that helped transform Head-Royce. Standing on the shoulders of so many who worked so hard to help the school survive and thrive, we turned our attention in the mid-1980s to challenges of building, funding and managing the school that would shape Head-Royce for decades to come.

Head-Royce today is devoted to its historic mission and is building on over 130 years of success. The school exemplifies a dedication to excellence in its daily life, and encouraged by the new strategic direction is helping to develop citizen leaders who will make a significant contribution to the nation. For Head-Royce School, the future is bright.

This article is adapted from School Matters: The Transformation of Head-Royce School (Berkeley: Edition One Press, 2018) by Paul Chapman. Copies of the book are available from Head-Royce School, Julie Kim-Beal, Director of Alumni Relations, jkbeale@headroyce.org).